Good Design: Going-to-the-Sun Road

Glacier National Park is located in northwest Montana, and is known for its expansive views of majestic mountains, sharp valleys, and crystal-clear lakes and rivers. Since opening in 1910 [1], Glacier has seen many visitors come to visit these natural wonders. However, the advent of the automobile presented an interesting design problem for the park: how could visitors travel easily to and from each attraction in the park? Hiking and horseback were certainly options, but the growing popularity of cars led park leaders to commission a road that would connect one side of the park to the other. This road would need to cut through these sharp, rocky mountains through an easy route made for the everyday automobile.

In 1924, Stephen Mather (director of the National Park Service at the time) asked the Bureau of Public Roads to assist in designing and building a road that met these requirements. A National Park Service engineer named George Goodwin planned a route that included 15 switchbacks up a steep mountain on the west side of the park. Frank Kittredge, an engineer for the Bureau who was in charge of surveying (planning for and making sure the route was viable) the proposed route, recorded in his journal the magnificence of Glacier and the toughness of the challenge, noting that men completing the road survey had to climb 2,700 feet each morning before even starting work [2]!

Building the Granite Creek retaining wall in 1927 next to a sheer drop off [5].

Eventually, the survey was complete. Construction began near the entrance of the park, and before it reached the complicated switchbacks up the mountain, Mather, the park superintendent, and two other men came to inspect the progress. One of the men at this inspection was named Tom Vint, a National Park Service landscape architect. He proposed a new route for the road, requiring only one switchback and smaller grades up the mountain. The group was split in two opinions over which route should be built. Eventually, Mather decided to use Vint’s simpler route proposal and had Kittredge survey what is now the present route. This decision came with several drawbacks, including additional expense, time, laborers, and risk because of the increase of tooling needed to drill out more rock from the mountain for the lower grade and fewer switchbacks.

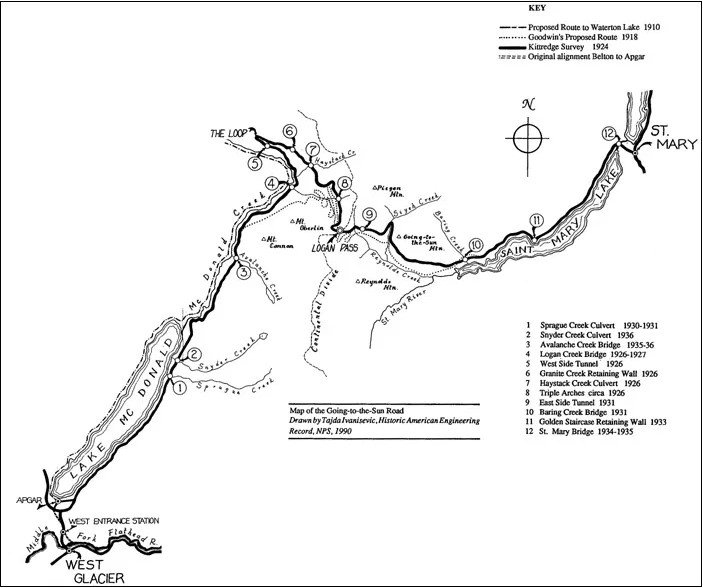

Map of the road, showing the one main switchback (named “The Loop”) [5]. You can see Goodwin’s proposed route in the small dotted line with 15 switchbacks - imagine driving all of those along the edge of a cliff!

Although construction was difficult, the road was completed in 1933. Today, more than 600,000 cars per year drive on Going-to-the-Sun Road [3], named for its view of Going-to-the-Sun Mountain (this mountain got its name from one of two theories: the theory that the Blackfeet god Napi ascended to heaven from this mountain, or the theory that explorers in the 1800s named it for its views of the scenery from the top [4]). The completion of the road now allows tourists to travel to attractions such as Hidden Lake, St. Mary’s Lake, Logan Pass, and many other trails that would have otherwise been hard to get to without a road. The road permits cars to travel across the park in two hours rather than taking a longer route around the mountains. Here are some photos of the original road construction, as well as some of the scenic views that are visible from parts of the road:

The road was originally finished with gravel, and later paved after WWII. [5]

View from the Garden Wall section of the road (taken by Jeremiah Sanders).

View of part of the road and scenery as it ascends to Logan Pass (taken by Jeremiah Sanders).

Key Takeaways

The design and construction of Going-to-the-Sun Road contains several lessons for designers and engineers today.

Simplicity

Complex designs can solve grand challenges, but simple designs can do the job just as well. In the case of Going-to-the-Sun Road, a simpler route with less hairpins was chosen. This decreased the chances of drivers crashing around more hairpin turns and made it easier to enjoy the views that the park offers.

Trade-offs

Opting for a simpler design may come with some trade-offs. In this example, the simpler route cost $1,000,000 more than the original route and came with more construction challenges and risks. However, these trade-offs are often worth the reward, as is the case in this example.

Long term reward

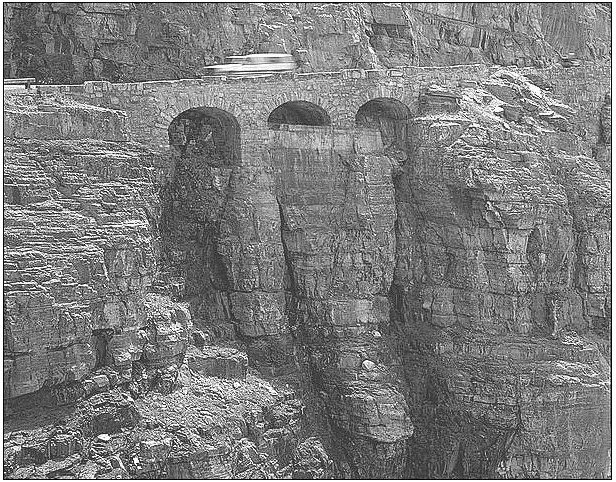

Thinking about the long term while designing can often yield great results. The designers and engineers of this road had the long term life of the park in mind, and designed a road that was easy to use and that blended in with the landscape of the park to provide an enjoyable, natural way to cross the park. For example, the arches used to support the road were designed to blend in with the mountain.. This long term thinking continues to pay off as the road is used today!

Triple arches supporting the outer edge of the road using the rock architecture provided by nature [5].

Don’t be afraid to propose new, innovative thinking

Engineers with minimal experience still have valid ideas and proposals. Design is often held back because these engineers will hold back their ideas, opting to listen to a lead engineer! Vint, a less experienced architect, proposed a more challenging yet innovative route instead of settling for the design of the more experienced engineer. His courage has paid off!

Going-to-the-Sun Road is an excellent example of good design, and learning about its history provides valuable lessons for our modern day design challenges. Using innovative thinking and challenging what is possible paid off, and the road now provides enjoyment for the millions of people who visit the park each year.

References

[1] The History of Glacier National Park: Crown of the Continent, Montana PBS, https://www.montanapbs.org/programs/historyofglaciernationalpark/, accessed 9 September 2022.

[2] Surveying Going-to-the-Sun Road, National Park Service, https://web.archive.org/web/20151005024858/http://www.nps.gov/nr/twhp/wwwlps/lessons/95sunroad/95facts1.htm, accessed 9 September 2022.

[3] Going-to-the-Sun Road — an Engineering Feat, National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/glac/learn/news/upload/Going-to-the-Sun-Road-An-Engineering-Feat.pdf, accessed 9 September 2022.

[4] Climbing Going-to-the-Sun Mountain, Hike734, https://hike734.com/trip/climbing-going-sun-mountain/, accessed 9 September 2022.

[5] Going-to-the-Sun Road: A Model of Landscape Engineering (Teaching with Historic Places), National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/articles/going-to-the-sun-road-a-model-of-landscape-engineering-teaching-with-historic-places.htm, accessed 9 September 2022.

To cite this article:

Sanders, Jeremiah. “Good Design: Going-to-the-Sun Road.” The BYU Design Review, 9 Sep. 2022, https://www.designreview.byu.edu/collections/good-design-going-to-the-sun-road.