Good Design: The VODA Heat Powered Stove Fan

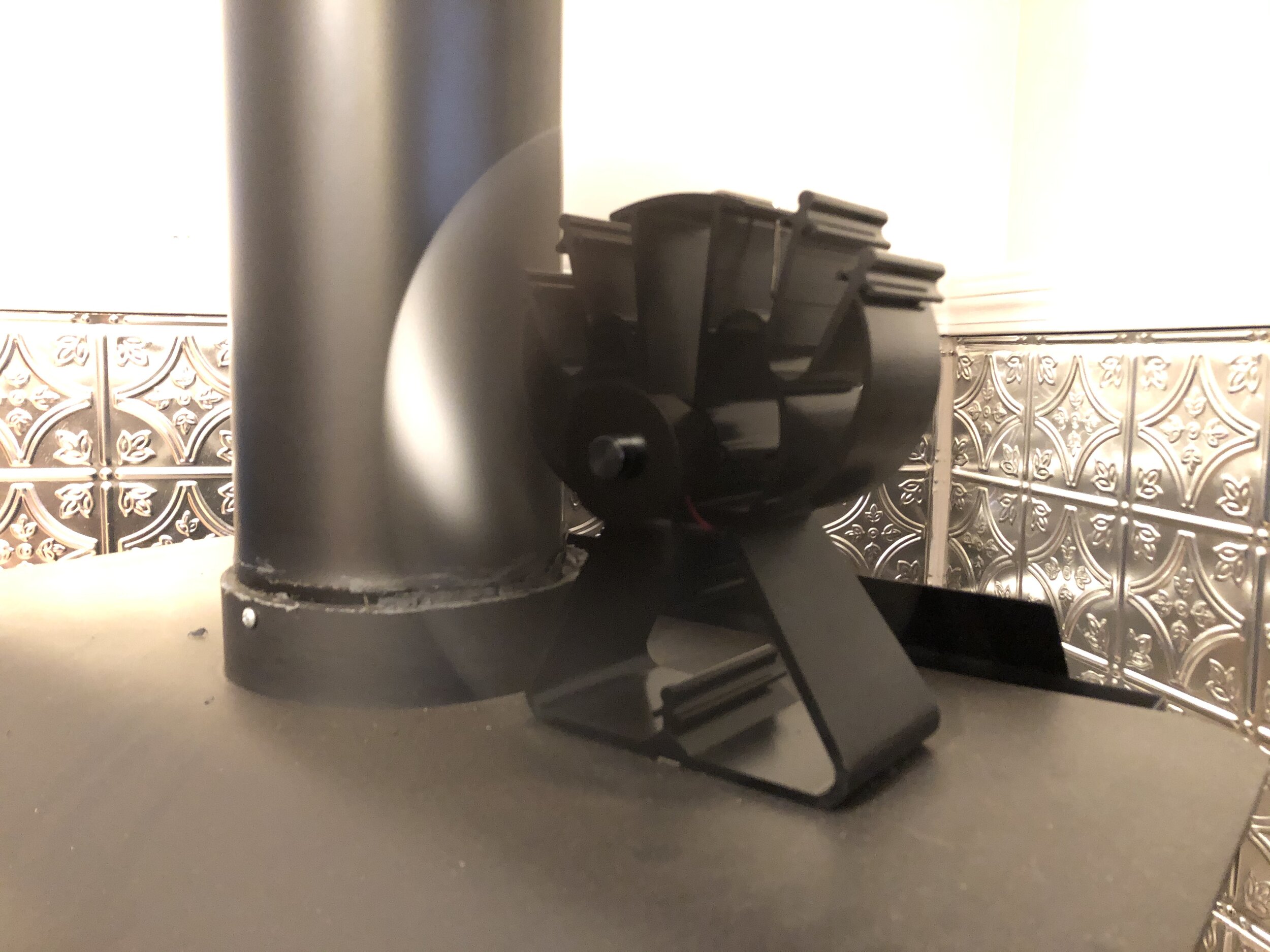

My Aunt and Uncle installed a wood burning stove in their basement, and I got to check it out over the holidays. The stove looked great and they did an excellent job installing it. As I was admiring their work, this little fan caught my eye-

What you see on top of the stove is a heat powered stove fan by VODA, one of the several companies that produces heat powered stove top fans.

A common deficiency in heating a room with a wood stove is that the heated air accumulates around the ceiling or dissipates off of the exhaust pipe instead of spreading out to fill the room. Stove top fans solve this problem by blowing hot air next to the stove into the rest of the room. They reduce fuel consumption up to 20% and warm up the air in the room 30% faster [1].

Some stove top fans are electric, but as the title implies VODA’s heat powered stove fan draws its power from heat emitted off the stove it’s next to. Let’s look into the relationship between the fan, the stove, and the consumer for design principles we can apply to our future projects.

Symbiotic relationships as a model for powering your product

In nature, a symbiotic relationship is a long-term interaction between two different species [2]. Scientists consider there to be 6 types of symbiotic relationships; we will consider 3 symbiotic relationships and use them to describe relationships between different products.

Parasitism describes a relationship where one species benefits and the other is hurt in some way (looking at you, BBQ porch mosquitos). Mutualism describes a relationship where both species benefit. A good example in the animal kingdom could be crocodiles and plover birds. The plovers eat leftover food in the crocodiles’ mouth and the crocodiles are relieved of oral hygiene threats. Finally, commensalism describes a relationship where one species benefits, and the other is neither hurt nor benefitted. For example, remoras live around sharks and other large marine animals. A suction cup on top of the remora’s head allows them to attach themselves to a host for transportation, and remoras eat feces and leftover food scraps from the host. The hosts, such as the bull shark below, remain ambivalent to their presence [3].

Moving from the world of organisms to mechanical design, the stove fan and the wood stove are in a mutualistic relationship. Heat from the stove supplies power to the fan, and in return, the fan increases the efficiency of the stove. This relationship would not be possible without thermoelectric generators. Thermoelectric generators convert a temperature difference (heat energy) into a voltage difference (electrical energy). The relationship between temperature gradients and electricity was first discovered in the 1820s by Thomas J Seebeck. Seebeck noticed that when two different metals were connected, then exposed to different temperatures at each end, it would create an electromagnetic field. He could measure the strength of this electromagnetic field by how much his compass would deflect. Years later with the discovery of the electron, physicists realized that Seebeck’s experiment was producing a circuit. Electrons travel from the hot end towards the cold end, creating a voltage source proportional to the temperature difference of two metals [4]. For the fan, the electric energy in the circuit can be converted into mechanical energy to spin the propellers.

Where else can we “see” symbiotic relationships in product design? Hybrid vehicles draw from a commensalistic approach. When the brakes are applied in a hybrid vehicle, the motor shaft is put into reverse. Spinning backwards, the motor generates electricity and charges the car’s battery. The braking system sees no negative benefit from this relationship, but the entire car benefits from increased gas mileage. Currently, scientists are studying wearable tech that converts chemical potential energy in human sweat to electric power for wearable devices [5]. Too much of today’s energy is parasitic, such as coal powered electricity or gas-powered vehicles which produce greenhouse gases at the expense of our planet. Our first lesson from the stove top fan is that the best designs strive for a sustainable, healthy, power source.

Aesthetic and Safety

The lack of a power cord contributes to the fan’s simple look and safety. I learned about the aesthetic and safety challenges involved with wires and cords as an intern wiring control panels. These panels could be anywhere from a foot square to ten by five feet, and the largest project I got to be a part of required 2 miles of wire over ten panels. The hours I spent bundling wires together and laying them out in wire trays taught me that professionally presenting your work gains the client’s trust. Even if a disorganized panel functions the same as an organized panel, consumers and clients are less likely to trust a sloppy panel. Furthermore, having organized wires reduces the likelihood of future errors when repair personnel or field operators use the panel down the road.

The relationship between aesthetic and safety is at work in the airline industry as well. Consider the paint on a Boeing 747. The paint coat on a Boeing 747 weighs 555 pounds dry and costs $200,000 to paint, including labor [6]. Given that paint does absolutely nothing to increase lift or thrust, this sounds absurd for an industry where every pound counts. However, painting planes is an essential part of protecting the plane body (UV and corrosion protection, internal temperature mitigation with lighter color paints) and establishing a brand that denotes safety and comfort [7].

Bringing it back to the stove top fan, imagine that the fan was powered by a 120V outlet in a common American home. You now need to add a power plug and must deal with the following questions:

Where is the best spot to put the power cord?

How long should the cord be?

Could the rubber melt around the cord? Furthermore, what UL and NFPA codes do I need to comply with to make this cord safe around heat?

The list would go on and on. A power cord would have been ugly, posed safety concerns, and distracted from the clean, sleek image of VODA’s fan. Our second lesson from heat powered stove fans is that fulfilling aesthetic and safety requirements are two sides to the same coin and essential to product development.

Consumer Experience

Have you ever had a product you absolutely loved… but stopped using it because the batteries died, and you never picked up new batteries at the store? Or did you stop using it because it was difficult to set up, use, and put away? Half the flashlights I own are sitting in some forgotten drawer because their batteries died. As much as I like shredded cheese in my food, I avoid using my cheese grater because it is a pain to clean. Many products stop getting used because in one way or another, they are a hassle.

The easier it is for a person to set up and use your product, the more they will love it. The stove top fan turns itself on and off as the stove heats up and cools down. All the consumer needs to do is set the fan on the stove and walk away— no batteries or button pushing required. Furthermore, the fan is quiet, letting the stove owner go about their regular activities without any kind of disturbance. All these little decisions add up to a product the consumer trusts and relies on. Our third and final stove top fan lesson today is that designers should do all they can to simplify the user’s experience with their product.

Conclusion

Design is a broad field. In this article, we’ve covered crocodiles, 747s, dead flashlights, and (tried to?) relate them to stove top fans. VODA’s heat powered stove fan reminds us of the importance of efficient power, aesthetic and safety, and user friendliness. Kudos to VODA for making a good first impression with their product and blowing me away with their design.

Editor’s Note: This article is part of a new series on “good design” where we highlight products, systems, and services that embody design principles worth aspiring to. We invite our readers to submit a Good Design article to the BYU Design Review, in hopes that over time we will collect a large number of articles that inspire and instruct us toward better design.

Notes:

https://householdair.com/best-wood-stove-fan-no-electricity/#:~:text=If%20you're%20not%20sure,doesn't%20require%20a%20battery. Accessed December 28 2020.

Wikipedia, Symbiosis, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Symbiosis. Accessed December 29 2020.

Encyclopedia Britannica, Commensalism, https://www.britannica.com/science/commensalism. Accessed January 11 2021.

Wikipedia, Thermoelectric effect, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thermoelectric_effect. Accessed December 29 2020.

IEEE Spectrum, Why Sweat Will Power Your Next Wearable, https://spectrum.ieee.org/semiconductors/devices/why-sweat-will-power-your-next-wearable. Accessed December 29 2020.

The travel stats Man, The $200,000 Paint Job. https://www.travelstatsman.com/06052019/the-200000-paint-job/#:~:text=Amount%20of%20paint%20required,and%20that's%20after%20it%20dries. Accessed December 28, 2020.

“It's time-consuming but essential work because an airplane's livery is a highly visible manifestation of its brand. When Gordon Bethune took the reins at Continental Airlines in 1994, the company was just weeks away from insolvency but he had the fleet repainted. He believed planes that look like crap send the message that the airline is crap.” Wired, How to Repaint a Jumbo Jet in 3 Minutes, https://www.wired.com/2009/01/how-to-repaint/. Accessed December 28 2020.

Picture credits:

Crocodile and Plover Bird: https://smallscience.hbcse.tifr.res.in/crocodile-and-the-plover-bird/

Bull Shark and Remoras: Fiona Ayerst, Shutterstock

To cite this article:

McKinnon, Samuel. “Good Design: The VODA Heat Powered Stove Fan.” The BYU Design Review, 12 Jan. 2021, https://www.designreview.byu.edu/collections/good-design-the-voda-heat-powered-stove-fan.