Why Study the Design Process?

I am a sucker for reading the introductions or prefaces of textbooks. I’m always curious — after writing an entire book, and dedicating who knows how much time to write it — what else does the author want me to know?

A few months ago, a professor in the engineering department retired and I inherited his stack of design textbooks. There is so much written on the subject of engineering design, and this is only a small sample. Why would you undertake a deep study of engineering design, or the design process, when you could go about design on your own and learn from your own experience? Who really needs all these textbooks?

In the ~~ introduction ~~ of Clive Dym and Patrick Little’s book Engineering Design, I read something that I believe addresses these questions:

“Some of our friends and colleagues in the profession like to point out that the tools we teach would be unnecessary if only we all had more common sense. Notwithstanding that, the number and scale of failed projects suggests that common sense may not, after all, be so commonly distributed.” [1]

It’s very hard to beat hands-on, common sense experience. But Dym and Little suggest that there is value to be gained from studying design, and I want to add my own take on why studying design is an important complement to hands-on experience.

Design Methodology

Design is the iterative cycle of creation and evaluation. And it holds true for just about every type of design. Regardless of what’s being designed, the designer creates something, evaluates its worth, and repeats until they are satisfied. Engineering design takes on extra meaning, as its goal is to “create a desirable technical solution that meets stakeholder needs” [2].

Methodology is defined as “the body of methods, rules, and postulates employed by a discipline” [3]. Put together, design methodology is the study and science of design. It covers how to design something, the best practices for designing it, and how individuals and teams can navigate the design process.

So… Why Study Design Methodology?

When someone tries to teach design as a discipline or a study, it is sometimes met with resistance. A common critique is that the instructor makes design too complicated. When I took my senior capstone design class, I would hear things like, “design isn’t this complicated in the real world.” Or, “in industry, you don’t actually do this. This is what you do…” This sentiment is similar to the criticism Dym and Little hinted at in their introduction. Yet, many engineering projects fail— both in college settings and in professional ones.

I believe that studying the design process addresses these failures. A high-level, abstract understanding of design enables the engineer to see their product as a concept, or a system, with interacting parts. The designer sees how the concept needs to evolve from an idea to a manufacturable product. This viewpoint lets the designer anticipate challenges before they happen, or the design actions needed to avoid failures.

For many expert designers, their design practice has become a routine, or a habit, and they might not be actively thinking about their process anymore. This could be why many practicing engineers say that a capstone course overcomplicates design. I think back to the engineers I worked for as an intern. It was amazing to see the design habits they practiced after decades of experience in the field. When I compared the processes, methods, and activities that I learned in capstone to what I saw at my internships, I realized that while completely different on the outside, I could identify the core principles of design at work on the inside. It’s realizing, acknowledging, and practicing these principles that enable an engineer to approach new challenges with confidence and skill.

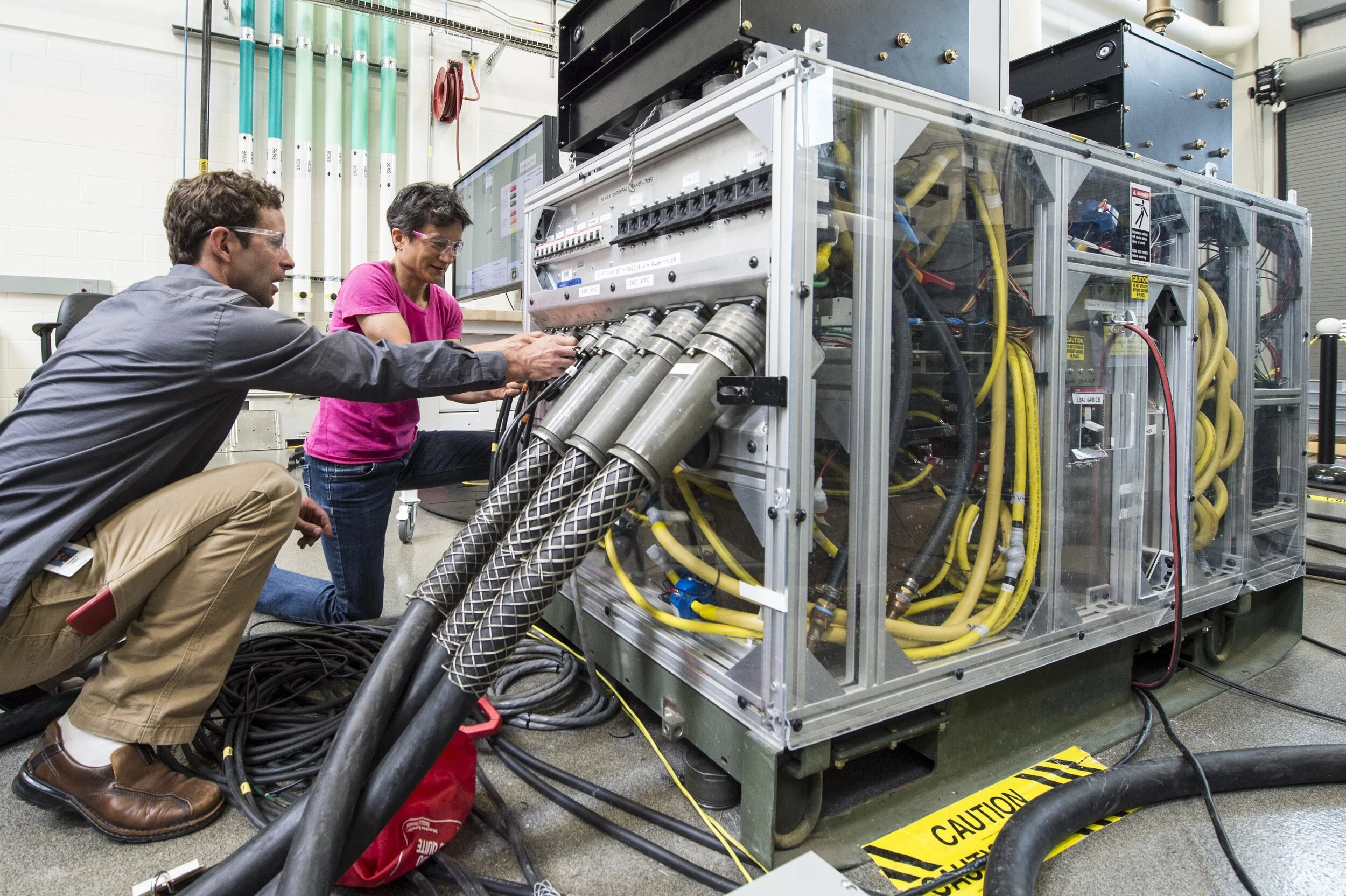

For example, I once watched a professor design a machine that would assist our lab’s research. The design required an understanding of kinematics, mechatronics, and mechanical design. The scope of the project was something that would have taken a 2-3 student team one semester. However, I watched this professor create the machine in a month and a half.

What stood out to me was the professor’s process. Rather than starting at a sporadic point along the design process, they were deliberate about each action they took. They had a refined concept detailed out in sketches and writing, with subsystems and their interactions identified. As they began making CAD models and 3D printing the components, they systematically tested each part or component to make sure it worked before continuing. This allowed them to realize, troubleshoot, and solve problems in a quick manner (as opposed to waiting until the assembly was completed to test everything, and having little idea as to what went wrong).

In Conclusion

Before closing, I also need to say that there is much benefit to be gained from mastering a specific domain or area of interest in engineering design. If you’re working at a company designing pressure vessels, you should master the codes, procedures, and processes regarding pressure vessels. Engineers are expected to be technical experts in their fields, and this will often require your best, intentional effort.

As you move forward with the mastery of your field of expertise, don’t lose track of your process. Many experienced engineers end up excelling in a specific domain and mastering the design process. Be cognisant of what actions are required, what you are doing, and how you are evolving the design. Afterall, every designer has a method. Studying the methods, and deliberating practicing them, just may take you to the next level.

References

[1] Clive Dym and Patrick Little. Engineering design: A project-based introduction. John Wiley & Sons, 2004. (I referenced the second edition. However, there is a fourth edition that came out in 2013.)

[2] Christopher Mattson. Engineering Design Essentials. 2023. See also Iteration: The most important concept in design and Mechanical Design on the BYU Design Review.

To cite this article:

McKinnon, Samuel. “Why Study the Design Process?” The BYU Design Review, 10 Apr. 2024, https://www.designreview.byu.edu/collections/why-study-the-design-process.