Golf Ball Dimples - A Design Feature for Distance

Why does a golf ball have dimples? Don’t you usually make things smoother to be more aerodynamic? The modern golf ball has dimples to help your drive go further, but it took a little curiosity and engineering to make the dimple a standard feature on the golf ball.

When golf was first played in Scotland in the 1100’s, the ball was made of a hand-sewn leather, filled with compact feathers, and painted white. This type of ball, called a featherie, flew 150-175 yards but was totally useless once it got wet. In 1845 the less expensive gutta-percha ball was introduced. It was made by heating and forming a smooth ball from the gum of the Malaysian Sapodilla tree, however, it still didn’t fly any further.

By the early 1900s professionals noticed that damaged balls, with small cuts and scratches, tended to go further than new ones. In fact, balls were commonly produced with all sorts of fancy or irregular patterns on them. These designs seemed a little too haphazard for the analytical mind of one successful businessman named William Taylor, who had taken up golf on the advice of his doctor that he find a relaxing hobby. In the 1930s, Taylor began his quest to find the surface pattern that would achieve optimal flight for the golf ball.

Taylor used a very scientific approach, building a wind tunnel in which he could observe smoke as it blew over balls. By studying the airflow around balls, he discovered the overall flow around the ball could be improved by adding a simple pattern of regularly spaced indentations over the entire surface of the ball, which, at the suggestion of his wife, became known as the “dimple ball”.

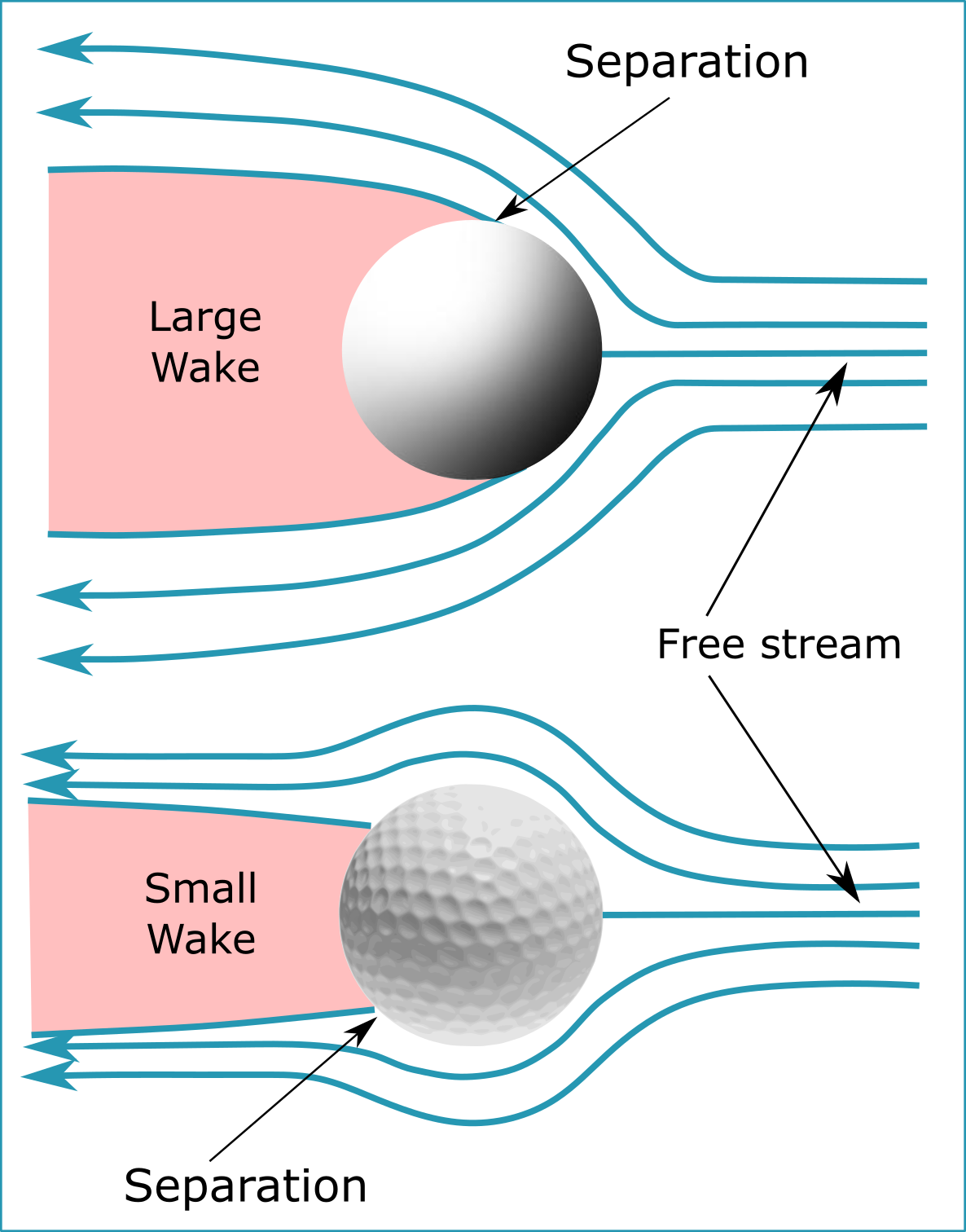

To understand why the dimple is effective at reducing overall aerodynamic drag, it helps to know that when golf balls fly through the air, the flow around the ball is generally smooth, or laminar, near the front of the ball and turbulent near the rear of the ball. When the flow transitions from smooth to turbulent, the flow around the ball begins to separate significantly from the surface. This produces a turbulent wake behind the ball that slows it down. It is a common aerodynamic design objective in most settings to delay flow separation downstream as long as possible.

For smooth balls, flow separation occurs closer to the front of the ball, while for dimple balls, the overall flow separation occurs further downstream, which results in a smaller wake, with reduced drag, allowing it to fly further.

The dimple itself is particularly interesting because it paradoxically creates small turbulent regions near the ball all over the surface - even in the front of the ball. This pushes fluid momentum closer to the ball, allowing the flow to stay attached and around to the backside of the ball. Although the dimples cause more turbulence near the surface of the ball, they delay the formation of the wake, creating a lower net drag which allows the ball to soar further.

Still today, new golf ball dimple patterns are designed which are intended to make your golf drive fly longer, drop quicker, or roll further. The world record is an amazing 515 yards by Mike Austin and that record has to thank dimples for a large part of that distance. But not even the best dimple pattern can help you sink that dreaded four-foot putt.

To cite this article:

Barnum, Garrett. “Golf Ball Dimples - A Design Feature for Distance.” The BYU Design Review, 11 Dec. 2019, https://www.designreview.byu.edu/collections/golf-ball-dimples-a-design-feature-for-distance.