Becoming Effective and Efficient in Your Work

I’ve been thinking a lot about what it takes to be effective/efficient in a technical profession. The most consistent part of my engineering career is that there has never been enough time to do everything that needs to be done. As such, efficiency and effectiveness are attributes I have been constantly reaching for. Of course I cared about this when I worked in industry – I wanted to make the best contribution I could. Now that I’m a professor, however, I care about this even more as I try to help the next generation make the most of their workplace experience.

When I think about being effective/efficient in a technical profession, one word comes to my mind: Fluency. Fluency means to do something with ease and accuracy. I would love to do mechanical engineering with ease and accuracy. I would love to sketch with ease and accuracy. I would love to solve partial differential equations with easy and accuracy. Those are worthy goals that would make me more effective and efficient in my work.

The concept of fluency is particularly meaningful when thinking about tools of the trade. Good carpenters are fluent with a framing hammer. Good dentists are fluent in reading x-rays. Good graphic designers are fluent with typography selection. And good accountants are spreadsheet fluent.

Being fluent and therefore doing something with ease and accuracy doesn’t mean that the work is simple or that anyone could do it. It means that a particular level of skill has been achieved and put properly into practice.

Becoming Fluent

To achieve skill and put it properly into practice, at least five things need to occur. You’ll need to first:

1. Know what a particular tool of the trade can do, and

2. Know how to make the tool do it

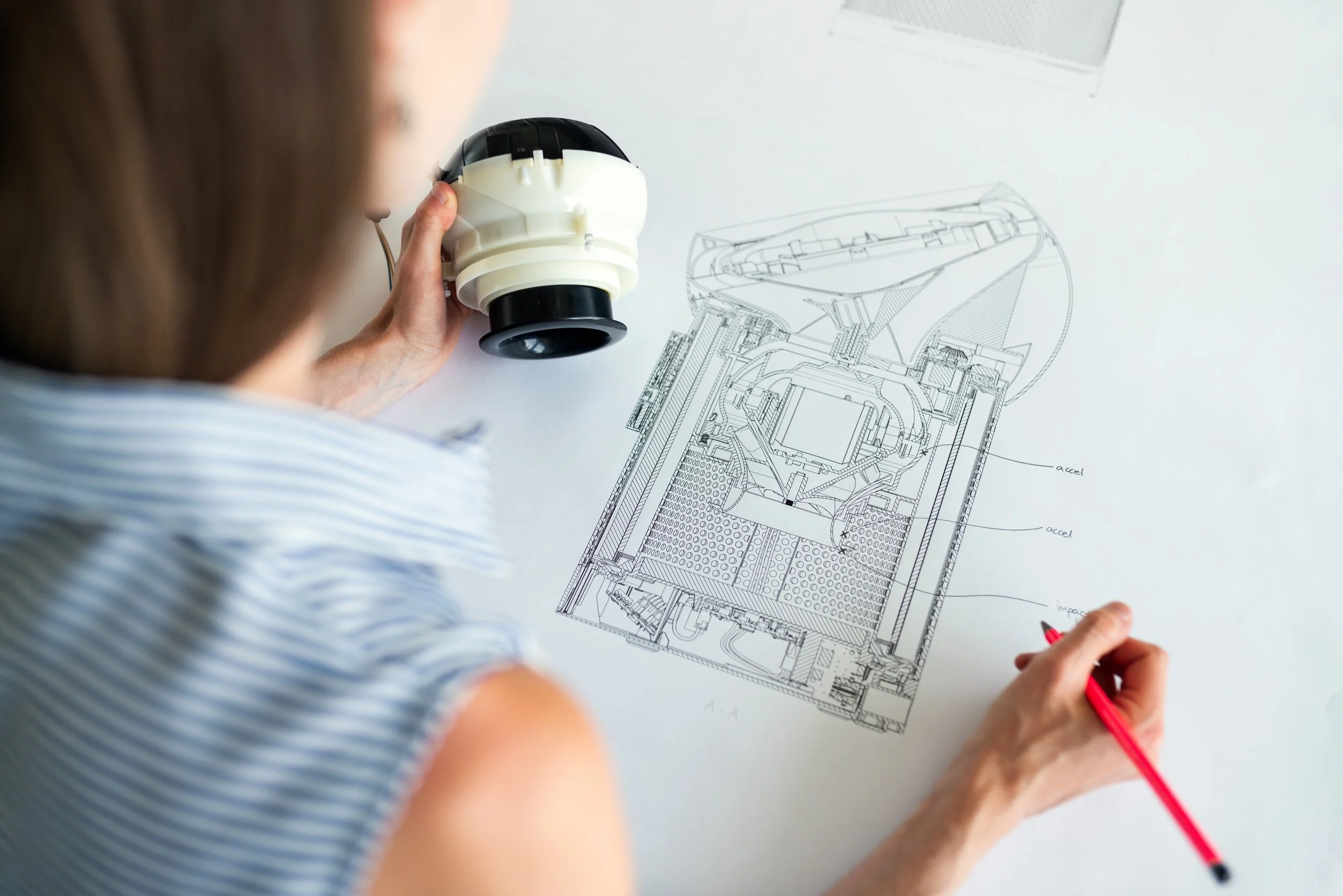

As an example, consider one of engineering’s most prolific tools – CAD. To use CAD to create a linear pattern such as the thumb grip shown below, you’ll first need to know that CAD software is capable of patterning geometry. If you don’t know that, you may find yourself creating each instance separately, which will require more effort and time. Thus without knowing about linear patterns, you’re less fluent in CAD than someone who does. Studying, exploring, and talking with people more experienced than you are excellent ways to improve basic fluency.

Linear Pattern Example in CAD

Just knowing about what a tool can do is not enough. You’ll also need to know how to turn the tool on or to make it do what it was designed to do. For CAD, this is often about knowing what buttons to click, and what inputs are needed to complete an operation. Fluency is highly related to this. You’ll spend more time and more effort creating the CAD geometry if you don’t know what is needed to execute a linear pattern or where the buttons are for creating one. Practice, exercise, and exploration are excellent ways to improve muscle memory and therefore fluency in this kind of area.

It is important to recognize that the two items listed above are the lowest level of skill. They are needed, but they are not the skills that will make you stick out as efficient and effective in your technical work. What will make you stick out are the three items listed below. For these, you’ll need to:

3. Know when the tool should be used

4. Know if the tool is working, and

5. Know what to do when the tool is not helping you as you hoped it would

My effective and efficient use of CAD will have a lot to do with using the right CAD operation at the right time. Using a shell operation, for example on the housing shown below, is a good choice when I want a constant wall thickness. If I don’t want a constant wall thickness however, a shell operation is a poor choice that will likely result in more effort and time to create the needed geometry. Furthermore, when (in the full set of operations) should the shell operation be executed? Before or after I cut out the LCD window? Knowing when a particular CAD operation should be used over another, and knowing in what order to execute operations highly influences one’s CAD fluency. Practice, critical self-evaluation, and developing a CAD strategy (a set of ordered operations that serve as a plan for model creation) are great ways to improve CAD fluency.

Order of Operation Shell Example in CAD

Point 4: Knowing if a tool is working as expected is also a fundamental part of fluency. Is it working? Did that work? How well did that work? These are all questions I hear efficient and effective people asking themselves almost constantly. These quick and frequent evaluations help us find small problems before they become big problems. Catching and fixing small problems before they require significant debugging and resources to resolve makes people more fluent – more capable of doing something with ease and accuracy. Being methodical, planning for quick and frequent evaluation, and being open to alternatives are useful for becoming more fluent.

Point 5: When using the tools of the trade, fluent professionals are able to systematically and often quickly resolve what went wrong if the result was unexpected or undesirable. They are practiced in examining the unexpected result and knowing what might have caused it, making an appropriate fix, and re-executing. To become fluent in this way, you need experience. This doesn’t mean you need industrial experience, it simply means you need to encounter problems and difficulties in your day-to-day work. The good news is that happens to all of us, almost all the time in our technical fields. Whether a student or a new professional, every problem and difficulty is an exercise in developing this highest form of fluency. Treating each experience that way is an antidote to mounting frustration and it is the key to becoming truly fluent.

Levels of Fluency

I find the five points listed above useful because they illustrate that fluency is on a spectrum. It’s not a matter of being fluent or not being fluent. It’s a matter of progression on the fluency spectrum. People who speak another language are often judged based on their level of fluency. Low levels of language fluency mean that someone is familiar with a few words but unable to structure sentences quickly, naturally, or even at all. People with high levels of language fluency can naturally carry on complex discussions on a variety of topics, often without a pronunciation accent.

Low levels of technical fluency would mean that I know where the CAD buttons are and what they do, but I am unable to structure a sequence of operations that put my button pushing skills to proper use. With only low levels of fluency, I can expect it to take more time an effort to create meaningful geometry, compared to someone with higher levels of fluency. High levels of technical fluency would mean that I can apply appropriate CAD operations to a wide variety of technical problems naturally with ease and accuracy.

Fluency is a Life-Long Pursuit

I love mechanical engineering, design, sketching, prototyping, CAD, and more. Although I have developed some level of fluency in these topics, there is still more growth ahead. That growth, however, won’t come without persistent effort and dedication. For example, I have to frequently explore the CAD software and make sure I am aware of what it allows me to do. I have to watch YouTube tutorials and read the help entries to know how to execute unfamiliar operations. I need to practice those operations in the context of complex projects that force me to think about if the use of the operation is appropriate, if it is working as intended, and to re-strategize, debug, and fix things when unexpected, undesirable, outcomes result. Just like language fluency, this requires practice and feedback. And a lot of it.

Is fluency worth the effort? Well, like most things, it depends on what you want. Recall that for me, I would love to do mechanical engineering, sketch, and solve partial differential equations with ease and accuracy. To me these are worthy goals that would make me more effective and efficient in my technical work. So for me, it’s worth it. I also like to consider the alternative, when deciding if it is worth it; would I be ok doing my engineering with difficulty and inaccuracy? Clearly the answer is no. Would I be ok outsourcing portions of my engineering responsibilities to people with greater skill and fluency? Yes, I am ok with that, especially given that I cannot afford to be fluent in everything.

To cite this article:

Mattson, Chris. “Becoming Effective and Efficient in Your Work.” The BYU Design Review, 1 Mar. 2021, https://www.designreview.byu.edu/collections/becoming-effective-and-efficient-in-your-work.