Sharing your Design Work

“Your primary job is to perform good design work, but a close second is to make it easy for other people to understand the work you’ve done. Neither of these is trivial, and neither should be underestimated. ”

The next time you need to share your design work, consider what your audience needs to do with the information you will give them. In most cases, they will be assessing the quality of your work in order to make a decision. The decision may be about whether the project is on track, or if additional resources would be well-spent if given to you, or whether you should get the promotion, or approve your request, or accept your solution, or shut down the project.

While the audience processes what you are sharing, they are attempting to answer some fundamental questions: What is the design? What does the design need to do functionally? How well does the design perform, and how do you know?

I have found that explicitly answering these questions while sharing your design work is very effective from all points-of-view and in nearly all scenarios. It is effective in industry and in academia, from the boss’s perspective and the designer’s, early and late in the design process, formally and informally, and in written and in oral formats.

The Fundamental Questions

When you present your work, make sure the answers to these fundamental questions are so unmistakably clear that no one could doubt you answered them well.

Question 1: What is the design?

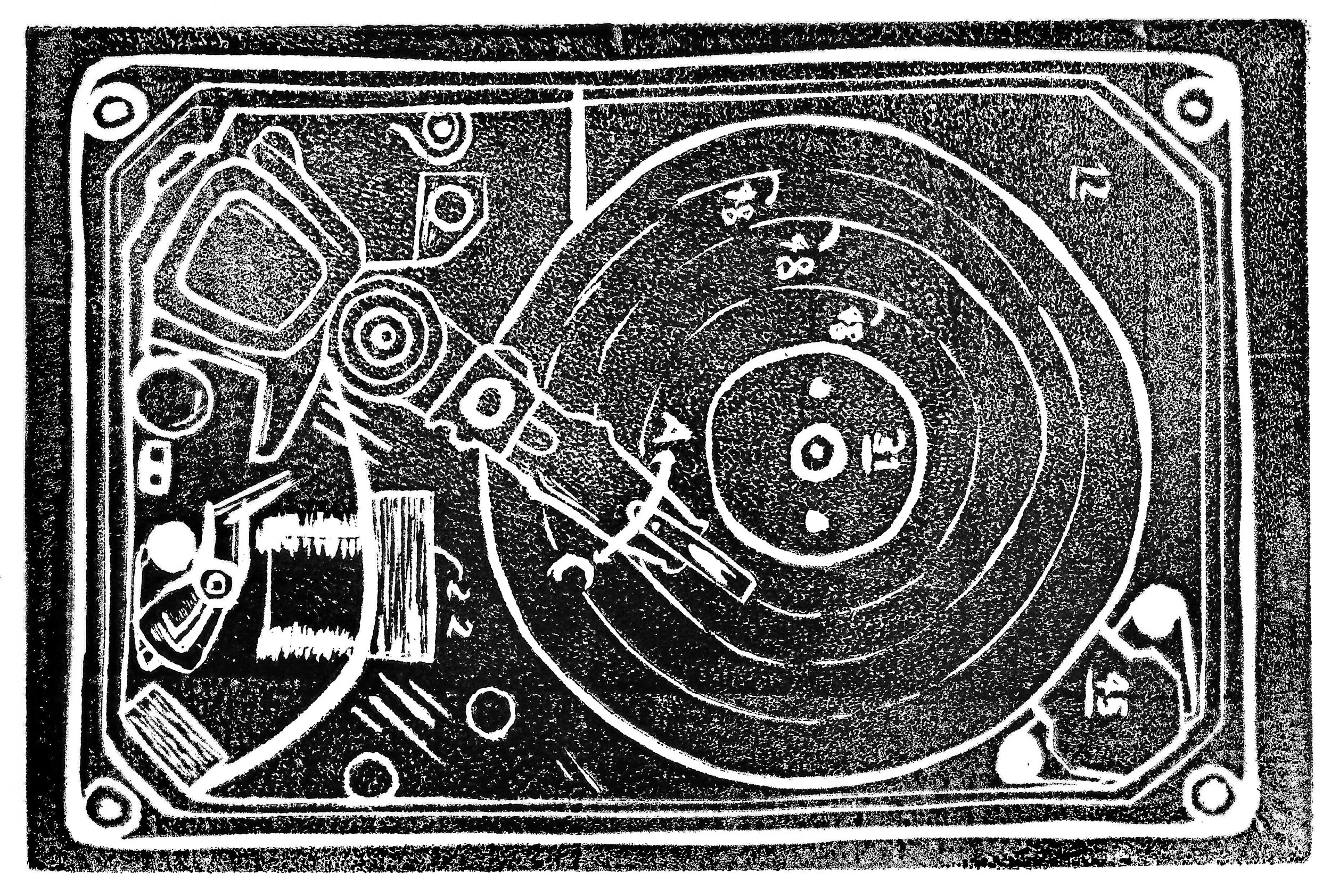

The design typically takes the form of a sketch, a rendering, a drawing, or possibly a vivid text-based description. The design often conveys information about its geometry, materials, required manufacturing processes, and its use. Make sure the audience is given clear and pertinent information about what the design is. If they don’t understand what the design is, then nothing else in the presentation matters.

Here are some ideas for conveying what the design is: Make a simple sketch. Show a schematic diagram. Show an exploded-view rendering. Put annotations on the visuals so the audience will pick up on the important parts of your message. Show a CAD model. Play an animation. Demonstrate a prototype. Display a storyboard. In every case, seek to convey your design quickly and in a way that requires minimal energy to adequately understand.

Relative to the other two fundamental questions, I have found it very effective to first describe the design (or result), followed by supporting information related to its function and performance. This is different than how scientific studies are presented, which typically provide background, hypothesis, test information before disclosing results and conclusions. Presenting the result first, followed by supporting information is called the Inverted Pyramid approach [1]. It is considered to be a more efficient way to share information.

Question 2: What does the design need to do functionally?

Here, I am referring to what the design needs to do to be considered desirable. This typically takes the form of requirement statements expressed as inequalities, such as the design needs to weigh less than a metric ton, or mass <= 1000 kg, fuel economy >= 30 mpg, and time between charges >= 16 hours.

If the audience doesn’t understand what the design is required to do, they cannot know precisely what you’re trying to achieve, and therefore cannot meaningfully judge the quality of your work.

When answering this question, your goal should be to make it easy for the audience to efficiently understand the pertinent requirements. I recommend using a table that combines the answers to Questions 2 and 3 together. Use the table to group similar requirements for quicker digestion. Highlight specific requirements that are pertinent to the discussion. It is useful to present what the design needs to do functionally and how well the design performs near each other so the audience can quickly assess what requirements have been met and which have not.

Question 3: How well does the design perform, and how do you know?

By how do you know, I mean what tests or other evaluations did you run to know how well the design meets the requirements. For quantitative things such as mass or length, a measurement is typically made and the measured values are reported as well as some information about the process and equipment used. For qualitative things such as makes the workplace feel safer or makes operation easier, interviews, observations, and/or surveys with people from the market are carried out and the results reported, also with some indication as to the process used.

Remember, if we can’t state how well a design works relative to the requirements, we can’t judge if the design is good. If we can’t state the method we used to determine how well a design works, then we are just guessing and expressing opinions.

When answering this question, try making a single table that presents the answers to Questions 2 and 3: List the requirement name in one column (mass), the numerical requirement in the next column (mass <= 1000 kg), the measured value in the next (measured mass = 984 kg), and simple statement in the last column with reference to a more complete study (I predicted the mass using SolidWorks mass properties of the entire assembly, see Vehicle Mass Properties Analysis in the appendix for more details).

Bookend with Context and Recommendations

The answers to the questions above will be best received when bookended by appropriate context and your recommendations for going forward. To establish context, get in the habit of providing a 10-second introduction to orient the audience to the project you’re working on, followed by another 10-second statement about what you would like to accomplish as a result of the presentation. For example, “This [meeting, document, video…] is for the Razor project, and specifically for the failed battery verifications tests, and our proposed fixes”, followed by “The purpose of this [meeting, document, video…] is to provide sufficient information for you to approve or reject our proposed fixes.” For the last bookend, remember that your audience will appreciate your statement/recommendations about what should be done next based on the information you presented.

The bottom line is this; when presenting your work, you need to answer these questions. If you don’t, your audience will be unsatisfied and will ask you them directly. Because they need to ask you these questions, they will likely conclude that you have not thought about them deeply enough, and that your design work is not as good as they hoped it would be.

REFERENCES

[1] W. Lidwell, K. Holden, and J. Butler, Universal Principles of Design, “Inverted Pyramid,” pages 116-117, 2003, Rockport Publishers.

To cite this article:

Mattson, Chris. “Sharing your Design Work.” The BYU Design Review, 29 Apr. 2020, https://www.designreview.byu.edu/collections/sharing-your-design-worknbsp.