Scared of Math

My PhD Advisor is one of my favorite people on this planet. He has had such a profound influence on me as a person, an engineer, a researcher, and professor. I owe so much to him, including how he shaped my appreciation for math.

To set the stage, imagine that you’re considering becoming an engineer. In your quest to learn if this would be good for you, you ask an older wiser person this question; what kind of skills do I need to be an engineer? The person answers “You need to be good at ____________”. There are a couple of common answers to this question, but one of the most popular is that you need to be good at math.

My education from kindergarten until graduating with my PhD represented 22 years of study. Every one of those years I studied math. But I didn’t study it very well, and for the most part math felt more like a stumbling block than anything else.

I was very scared

I am a bit embarrassed to say this, but it wasn’t until my first year of my PhD program, in mechanical engineering, that I became a mathematician. Ok, I had to look up the word “mathematician” to make sure I wasn’t overstating my relationship with math; A mathematician is someone who uses extensive knowledge of mathematics in his or her work, typically to solve mathematical problems. By the time I finished my PhD, this was a reasonable characterization of my relationship with math. Before that though, I was someone who used a basic – often broken – knowledge of mathematics to limp through engineering problems while mostly leaning on others to help me know if I was doing any of it correctly. I lacked confidence because of my poor grasp on math, so I mostly tried to avoid the hard stuff.

That’s where I was, embryonic in my skill and ashamed of my math, when I started my PhD.

During my PhD years, I spent all my days, and pretty much all my hours, in my research lab in the dark basement of the Jonsson Engineering Building at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in New York. The bright spot of that dark basement was my relationship with my PhD advisor, who spent a significant amount of time in the lab working with me side-by-side on our research.

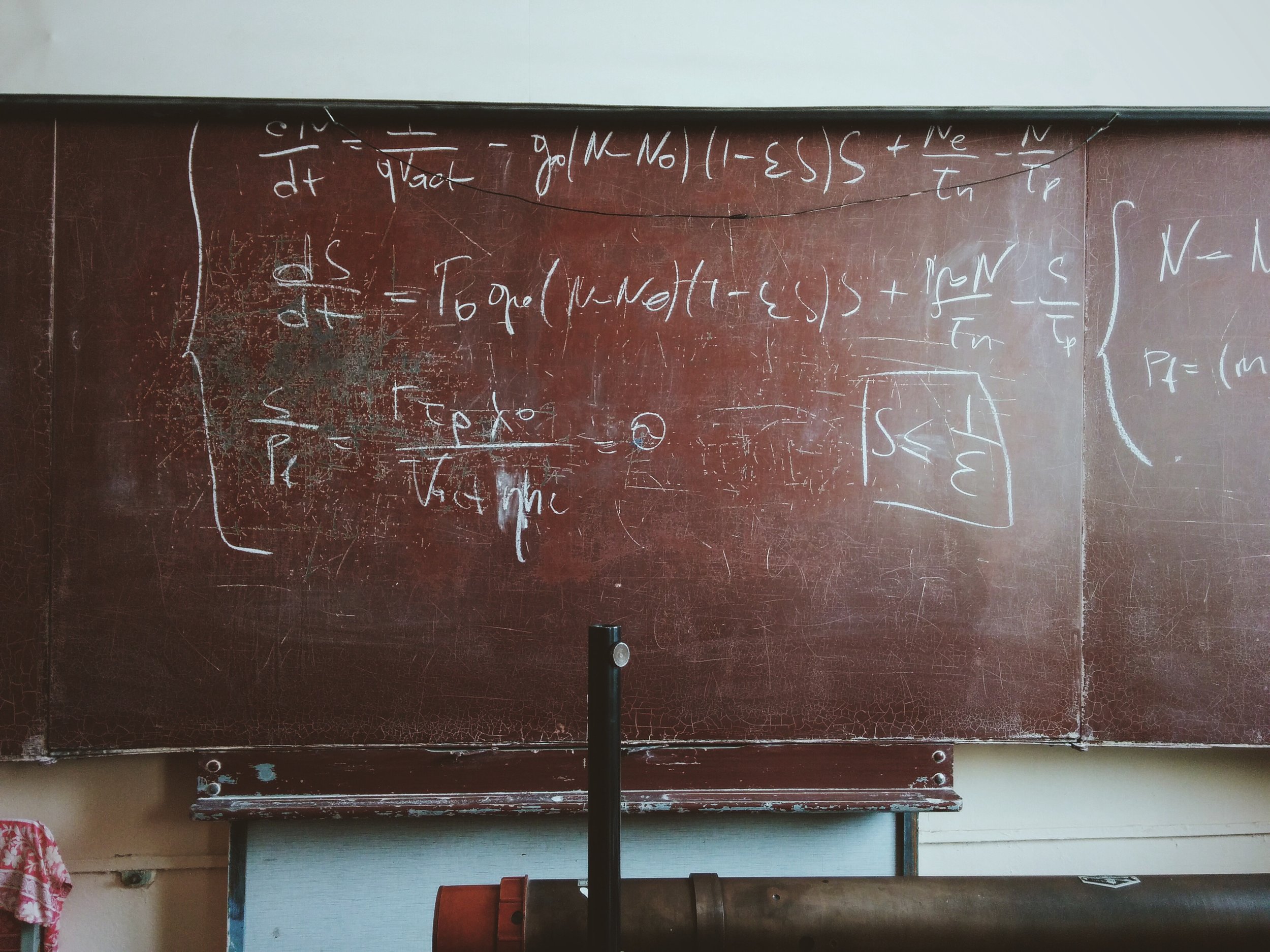

Sometime in the first year of working in that lab, my advisor and I were working on a project together, sitting at a conference table scratching out ideas on a piece of paper. After a long pause, which I thought was us simply pondering on the research—but now I realize was him trying to find the words to tell me I was troubled—he said “Chris, you’re scared of math, aren’t you?” Actually I was scared of math, but I said “No, I’m not scared of math”. He asked me a few kindly structured questions, mostly of the calculus variety, that exposed my weakness. And although I would not have chosen the word “scared” to describe my feelings about math, I was now very scared.

Maybe the only saving grace at that moment that kept me from just shrinking up and ceasing to exist was the fact that I was a good engineer. At that point, I had lots of industrial experience, and had great intuition regarding mechanical things. Sensing this, and in the most loving way imaginable, he said “Chris, as soon as you realize that math is a tool to help you in your engineering, you will love and embrace math.”

Almost instantly my attitude about math changed. It was no longer a test or a puzzle, it was no longer something I knew or didn’t know, it became a tool in my toolbox to help me achieve the goals that I was passionate about.

This shift in attitude changed my behavior. I soon found myself practicing math. Not for math sake, but for engineering’s sake. Not because I wanted to get some sort of top notch math grade, but because I wanted to become a top notch engineer. I found myself asking “how can I make better use of this thing called math?” and “where is my use of it weak, and how can I strengthen that weakness?”

One of the most important things I walked away with from this experience was an understanding that math is not a personal trait (just as a hammer is not a personal trait), even though I spent most of my education acting like it was. I stopped saying “I am weak, and I am slow at math.” And I transitioned into thinking about how this tool had gone under used, and about how I could use it better.

Why do I tell you such a personal story?

Many of you are headed back to school and are about to be put in an environment that will challenge your knowledge, expose your weaknesses, and encourage you to build new strength.

As you dive into that environment, I hope you’ll remember my experience with math and apply it to whatever subject is keeping you from reaching your potential. I hope that you’ll believe that math, CAD, thermodynamics, etc. are tools – not personal traits – that can be used to help you create something much greater than the tool. I hope you’ll see that attitude drives behavior, and that attitude is almost immediately changeable, as it was for me in that research lab when I chose to see math as a tool that would help me become a better engineer.

Not long after that experience with my PhD Advisor, I was in New York City and I saw an ad that said “Math is Power”. I remember this add because the letters M-A-T-H were tattooed on the fingers of a hand making a fist. With a tiny sense of victory afforded by my new attitude toward math, I too thought “Math is power”.

Now, however, after almost 20 years, I look back with a much larger sense of victory because I realize I had learned how to take any fear (not just the fear of math) and begin using it to strengthen me in meaningful ways.

To cite this article:

Mattson, Chris. “Scared of Math.” The BYU Design Review, 14 Aug. 2020, https://www.designreview.byu.edu/collections/scared-of-math.