Iteration: The most important concept in design

The context for design iteration

In its most basic form, the process of design is the same for all creative fields. The design engineer, for example, does the same basic thing as the music composer, who does the same thing as the web designer, who does the same thing as the sculptor.

The basic process is fundamentally about the iterative nature of creation and evaluation as shown below.

Figure 1: The synergistic interplay between creation and evaluation is part of all creative fields

1. Creation: In all creative fields, the designer creates. If it’s a design engineer, she might create a hand drill for the construction industry. If it’s a composer, he might write a song for a particular artist to sing. The web designer might create a virtual shopping environment, and the sculptor might create the bust of a prominent person in society. In every case, the act of creating is a fundamental initial part of the design process.

2. Evaluation: In all creative fields, the designer evaluates what he or she created, to see if it’s any good, and to expose its weaknesses. The hand drill, for example, may provide enough torque, but also cause undesirable pressure-points on the user’s hand. The composer’s song may fit the singer’s style, but is slightly out of her vocal range. The virtual shopping environment may be a promising path towards profitability, but be inaccessible to those with disabilities. The sculpture may be impressive, but inadequately represent the subject’s personality. Without a thoughtful evaluation of the work, potential areas of improvement are ignored, and the design work ceases to progress meaningfully.

3. Iteration: To advance toward greater desirability, all designers return to the act of creating to make improvements, which are then evaluated to see if they solved the weaknesses without creating new ones. This iterative and synergistic interplay between creation and evaluation is the basic process of design found in all creative fields. The iterative process (creation-evaluation-creation-evaluation) is continued until the result is sufficient, or until resources to continue development are exhausted.

Talk to any designer in any field and you will find that creation, evaluation, and iteration are at the root of what they do. Thinking of design in this way, allows us to see design everywhere, in turn allowing us to learn about design from various people of diverse backgrounds.

While considering design as the synergistic interplay between creation and evaluation exposes similarities across all creative fields, it is not detailed enough to distinguish between fields. What makes, for example, mechanical design [1] different than composing music? Or web design different than sculpture design? The distinguishing differences between these creative fields are in the design objectives, variables, methods, and tools for effective creation and evaluation. Consider the simple example in Table 1, which illustrates this point.

Table 1: Comparison of design objectives, variables, methods, and tools for mechanical design and music composition.

To be good at design, one must be thoughtful about how to use creation and evaluation synergistically to iterate towards a good design.

Iteration is the key to design success

If you think your design will be “right/good/complete/perfect” after just one cycle of creation, you’ll be disappointed and frustrated. It won’t be right, it probably won’t even be good, or be detailed enough to know how good or bad the design really is. If you accept that iteration is a normal, healthy, and expected part of the design process that should be planned for, your love for, and competency in, designing things will skyrocket [7].

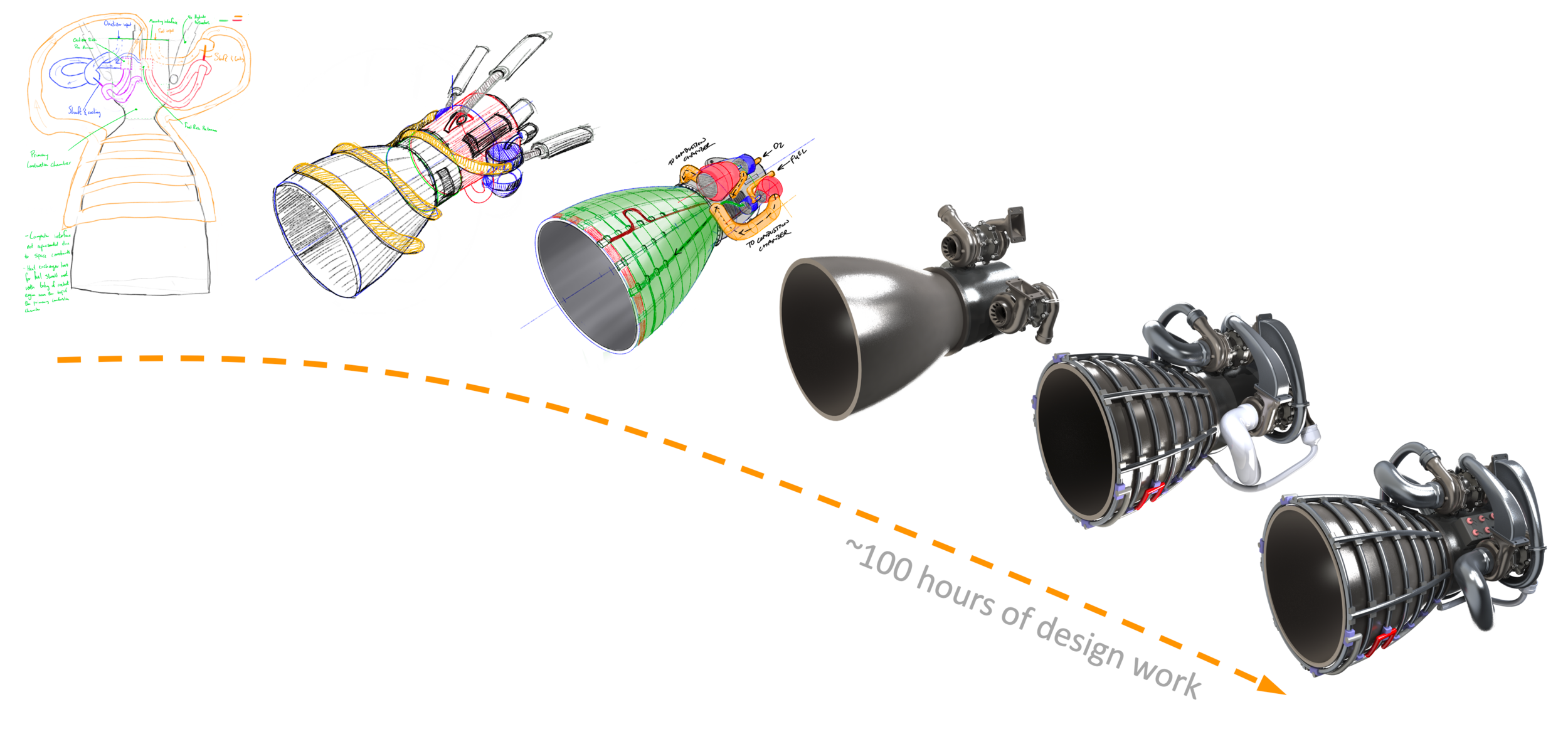

To put engineering design iteration into perspective, I’ve shared a few snapshots of a recent project to develop a conceptual rocket engine. I worked on this project with Nathan Woolley, who did the bulk of the design work and all of the CAD modeling. The following represents the progress after roughly 100 hours of design work.

Figure 2: A few snapshots showing design iteration of a rocket engine. CAD work by N. Woolley. Sketches by C. Mattson and N. Woolley.

Cultivating successful iteration

Successful iteration is driven by humility, insight, and feedback.

Humility: If you believe that your design is perfect, without flaw, and unimprovable, you will view iteration as a waste of time, and indeed – for you – it will be. All designs can improve, and humility is what enables it.

Insights: If you don’t seek to understand how well your design measures up – be it by exposing it to tests, analysis, or deep and critical review – you will never gain the insight needed to improve it. For example, it can be easy for nervous designers to only test their design under only one set of conditions. Imagine the insight that is gained from also pushing a design to its limits and beyond. That kind of insight opens the door for improvements that have a significant impact on the overall design success.

Feedback: If you’re the only one who critiques your work, you will likely be the only one who is satisfied with what you create. Since the goal of most design work is to benefit someone besides the designer, honest and critical feedback from others is an essential part of effective iteration.

Being open to humility, insight, and feedback is not easy. Resistance to these has a lot to do with the idea illustrated below, which, if understood, can be used to manage effective iteration. The figure shows two time-based curves; the designer’s openness to feedback (orange curve), which is high at the beginning of the design process and low at the end of the process. And the amount of the design that is thought to be set in stone (blue curve). Early in the design process, virtually nothing is set in stone, which makes the designer fairly open to feedback that helps define the design. Later, however, when a large amount of the design is set in stone, feedback is less welcomed. This is because late-stage design changes are often costly in terms of the work required of the designer. Obtuse feedback after this point is frustrating and often counter-productive. Both the designer and design managers should remember this.

Figure 2: Designer’s openness to feedback during the design process.

The reality of these curves means that the designer should take full advantage of the time before the dashed line is reached. The text under the horizontal axis shows that early in the design process frequent feedback should be sought [8]. Somewhere in the middle of the process (shaded area) the amount of design decisions set-in-stone rises sharply, and the designer’s openness to feedback simultaneously drops sharply. During this stage in the process, designers should seek feedback cautiously. Feedback relative to specifics are generally welcomed in this stage, but designers often feel that the time has past for feedback relative to changing major concepts and basic working principles. Later in the design process, after the dashed line, designers should seek approval and confirmation as opposed to seeking open-ended feedback since there is little freedom to change the design. To avoid frustration, both the designer and the design manager should avoid surprising each other, and other stakeholders, after the dashed line is reached.

The bottom line

Without iteration, design is superficial, ineffective, and unlikely to satisfy real needs. To make iteration effective, be humble, pursue insight, and know what kind of feedback to seek and when to seek it. Seek feedback about a design’s structure early and often. Seek feedback relative to design details in the middle of the process, and late in the design process avoid seeking feedback that will result in sweeping changes to the design. Instead seek final approval and confirmation that the design work meets the needs.

Above all, recognize that there comes a point in the design process where you will not be open to feedback. Understand where that point is for you and try to push it just past the moment where the bulk of the design decisions have been made and the design is largely set in stone.

Designers: Help those giving you feedback know what kind of feedback will be most helpful for effective iteration. It will be extremely helpful to let design managers know that you’re early in the process and open to large conceptual changes, or alternatively that you need feedback about small details relative to a fixed concept. However, also recognize that if there is significant doubt about the potential success of your selected concept, your manager will likely give feedback about the core concept, even if you don’t want it. You’ll need to become open to that kind of feedback.

Design managers: Engage in the project early by understanding the general concepts and working principles, while time-appropriate meaningful feedback can still be given, and while there is enough design freedom to react well to your feedback.

For the rocket engine project, we knew that the feedback early in the process would result in massive changes. For that reason, we used hand sketches to converge on a basic engine concept before jumping deep into the CAD work. Late in the design process, however, iterations centered on small refinements as shown in the feedback I provided this week.

Figure 3: Late-stage feedback focused on refinements as seen here. The right most image in Figure 2 shows what resulted from the feedback shown here.

References

[1] C. Mattson, “Mechanical Design,” The BYU Design Review, 2020, https://www.designreview.byu.edu/collections/mechanical-design, accessed 29 July 2020.

[2] Wikipedia, “Musical Composition,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Musical_composition, , accessed 29 July 2020.

[3] B. Martin and B. Hanington, “Bodystorming,” Universal Methods of Design, 2012, Rockport Publishers.

[4] Wikipedia, “Music Sketching,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sketch_(music), accessed 29 July 2020.

[5] C. Mattson, “Computer-Aided Design,” The BYU Design Review, 2020, https://www.designreview.byu.edu/collections/computer-aided-design, accessed 29 July 2020.

[6] Wikipedia, “Computer Music,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Computer_music, accessed 29 July 2020.

[7] T. Kelley, “Fail Your Way to Success,” The Art of Innovation: Lessons in Creativity from IDEO, America’s Leading Design Firm, Chapter 12, 2001, Doubleday, New York, NY.

[8] C. Mattson, “Two Dramatically Different Approaches to Design: From the Art of Innovation,” The BYU Design Review, 2020, https://www.designreview.byu.edu/collections/two-dramatically-different-approaches-to-design-from-the-art-of-innovation, accessed 29 July 2020.

To cite this article:

Mattson, Chris. “Iteration: The most important concept in design.” The BYU Design Review, 31 Jul. 2020, https://www.designreview.byu.edu/collections/iteration-the-most-important-concept-in-design.