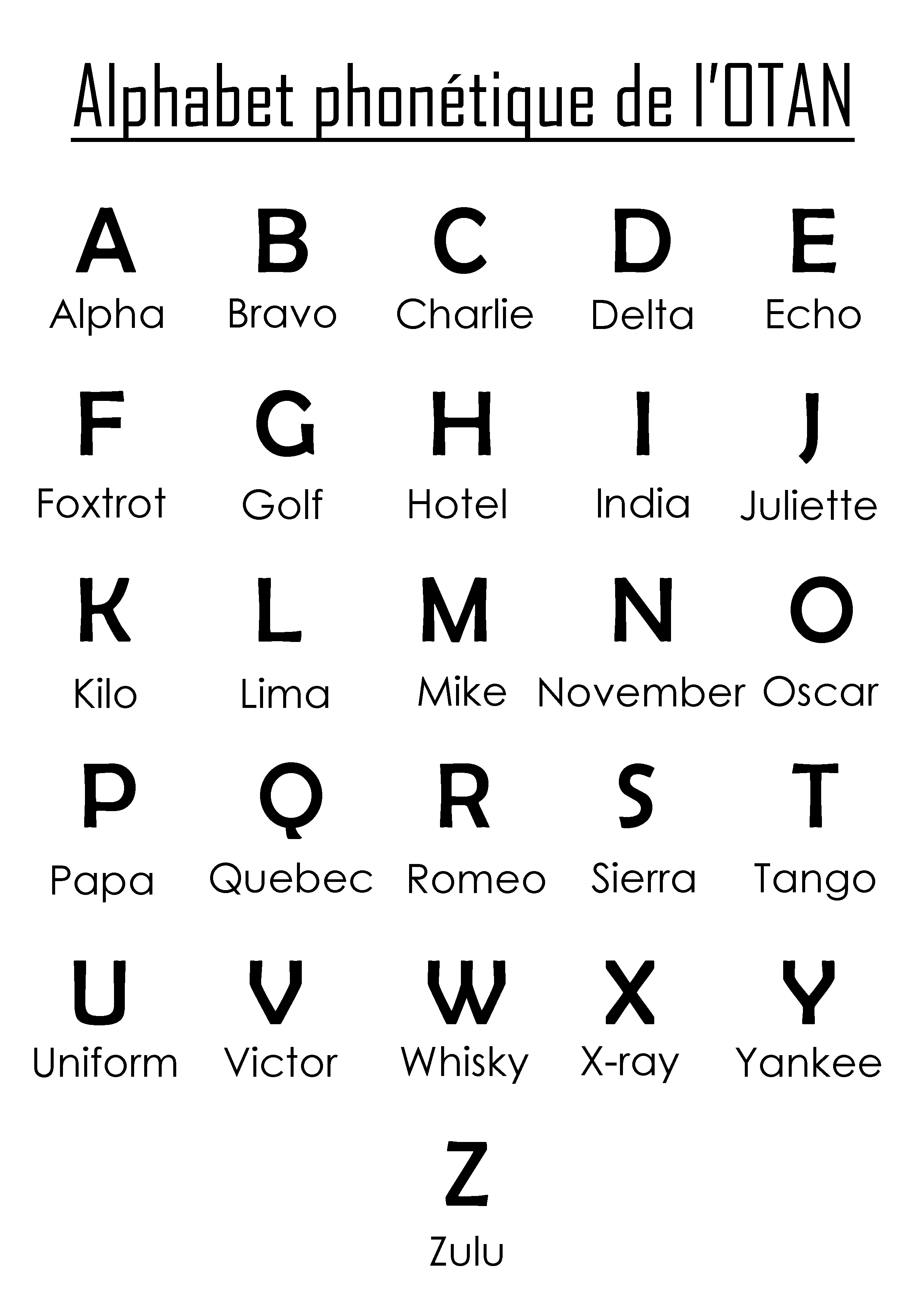

Good Design: Alfa, Bravo, Charlie, and The Phonetic Alphabet

Alfa, Bravo, Charlie, Delta, Echo… this is the NATO phonetic alphabet [1]. It has been used by pilots, air traffic controllers, military and other professionals around the world for the last 66 years—since 1956–without change [2].

The fact that the design has been internationally adopted, universally used, and endured for decades, indicates there is something good about it.

To be clear, the NATO phonetic alphabet was not the first such alphabet, but once its careful development was complete and put in place in 1956, it was widely and rapidly accepted by numerous international organizations and is still the standard today [3].

What made the NATO phonetic alphabet design so enduring that it survived the pre-digital (analog) age, and the onset and proliferation of the digital age? Why was this design so universal that it is used throughout the world with only minor regional adaptations?

In short, it solved a widely-observed problem (garbled radio communications). It did so by involving many global stakeholders. The design was the result of significant systematic testing and statistical analysis [4]. And the alphabet was adopted by an influential quasi-global organization (NATO), which pushed for its international acceptance.

The Problem

In 1876 Alexander Bell was awarded the first US patent for the telephone [5]. The first commercial telephones that soon followed were based on fixed wires between two places that wished to communicate. By 1891, AT&T had created a network of interconnected telephone lines that required switchboard operators and allowed for long distance calls to various locations [6]. As a young technology, telephony audio quality was full of static and plagued by audio intermittency making it difficult to clearly understand the spoken message.

To improve communication over the low-quality connections and possibly long-distance telephone lines of the late 19th century, basic telephone alphabets were developed [1]. These alphabets were used to spell out words by saying a full word for each letter of the alphabet. Thus making letters that were previously difficult to distinguish when named (such as the letters bee, tee, vee) more obvious (by saying beer, toc, and vic in their place [7]). As expected, this telephone alphabet system significantly reduced misinterpretation in telephone communication.

A few years later, in 1898, British military radio operators applied the idea of a telephone alphabet to two-way radio communications, but only assigned words to potentially confusing letters, namely A, B, M, P, V, S [7].

During the First World War, the miscommunication problem was made worse by the combination of noisy battlefield conditions and nascent radio technology. In short, critical radio communications were sometimes impossible to understand, because they had become muddled and obscured [8].

From this problem emerged the first versions of the radiotelophany phonetic alphabet— the alphabet that eventually became the NATO Phonetic Alphabet in 1956.

The Need for a Global Communication Standard

As miscommunication heighted during the First World War, significantly affecting lives and potentially influencing the outcome of the war, major efforts were dedicated to securing phonetic alphabet that was effective (correctly understood) and efficient (quickly communicated). But these development efforts were not centralized. For example, by the end of World War 1, Britain's Army and Royal Navy had two different phonetic alphabets to facilitate battlefield communication within their own military branch – but not with other branches. In the end, save the letter C - Charlie, neither of these phonetic alphabets endured [3].

The problem persisted when, during the Second World War, allied forces separately developed their own phonetic alphabets to improve communication internally [2], while, again, limiting unambiguous communication that needed to occur across allied forces. The US Military’s system was called Able Baker after the first two words of the alphabet, while the British Military’s system was based largely on that used by the Royal Navy in World War 1. Despite these individual efforts, communication confusion remained.

Good Design Begins

The US Military’s phonetic alphabet, Able Baker, was the result of significant research carried out by the US Air Force working with Harvard University’s Psycho Acoustic Laboratory [1, 9]. Their work focused on determining the most successful word for a letter to be represented by; both when interpreted through a military handset and amongst the noise of the battlefield. With this focus, the researchers proceeded to test and compare various existing phonetic alphabets under these conditions.

Scoping the problem to that of interpretation through the handset, and testing existing alphabets were important elements of good design process. But these good practices were not enough.

In 1943, the US, British, and Australian forces adopted a modified version of Able Baker and successfully used it to coordinate efforts for the rest of the war [1]. After the war, because of its wide-spread use, the modified Able Baker became the official international phonetic alphabet [2]. However, soon after its introduction beyond English-speaking US, UK, and Australia, it was apparent that many of the words in the modified Able Baker alphabet had sounds unique to the English Language. Even the words Able and Baker were switched to Ana and Brazil in Latin America [1].

The failure of the modified Able Baker alphabet was rooted in the fact that an international standard was set having only considered three, mostly homogenous, stakeholder groups (US, UK, and Australia).

An Organized Effort

Near the end of World War 2, in 1944, a convention was held called The Chicago Convention on Civil Aviation [10]. At this convention, 55 countries agreed to unified rules regarding airspace, safety, aircraft registration, and more. At this meeting, the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), was established [11] and soon become a key player in the development of the NATO phonetic alphabet.

At the end of the war, and during ICAO’s second year of existence, it adopted Able Baker and quickly observed global challenges associated with its favoring the English language. By ICAO’s third year, they had introduced a draft of a new phonetic alphabet that had sounds common to English, French, Spanish, and Portuguese [1]. By ICAO’s fourth year, recognizing the need for and having experimented with a more global alphabet, ICAO began working closely with expert Jean-Paul Vinay, a professor of linguistics at Universite de Montreal [9] to formally and systematically develop an effective and efficient phonetic alphabet for the entire world.

Prof. Jean-Paul Vinay

Here we begin to see good design practice emerge more clearly. For example, by its nature, ICAO involved many stakeholders (55 countries) who were focused on a clear goal: the development of a globally useful alphabet. ICAO worked quickly, making decisions, observing deficiencies, experimenting, and engaging experts in the years immediately following ICAO’s establishment. These practices significantly influenced the success of the eventual NATO phonetic alphabet.

Formal Design Requirements and Experimentation

ICAO’s 1948-1949 research with linguistics Prof. Vinay was substantial. The goal was a global alphabet and the requirements were clear. Each word of the alphabet was required to [1,9]:

Be a live word in each of the three working languages (English, French, and Spanish).

Be easily pronounced and recognized by airmen of all languages.

Have good radio transmission and readability characteristics.

Have a similar spelling in at least English, French, and Spanish, and the initial letter must be the letter the word identifies.

Be free from any association with objectionable meanings.

What resulted from the two year effort with Prof. Vinay was a full alphabet, including 17 of the words that remain today in the NATO phonetic alphabet. After significant in-field testing, Vinay’s alphabet still showed problems distinguishing between some words, such as Nectar and Victor.

To more formally identify deficiencies in Prof. Vinay’s alphabet a large number of tests were conducted by the US Air Force, which involved speakers from 31 countries [1]. Tests were focused on word articulation, and word confusability with other words in the set. For example, when testing alternatives for the word Foxtrot, Football scored slightly higher than Foxtrot in articulation, but was found to be more easily confused with Hotel and Victor [9]. Therefore the overall effectiveness (maximum articulation score and minimum confusability score) of Foxtrot was higher and it remained in the alphabet.

Attitudes relative to each word were also considered. Multinational people involved in the tests rated each candidate word for prejudice on a 7-point scale. A score of 1 represented high acceptance, while 7 repressed strong repugnance for the word [9]. After a six-week period of daily use, prejudice was retested to observe shifts in preference.

A wide suite of tests were carried out with native and non-native english speakers, with college-educated and highschool-educated people, as well as with military and non-military personnel [9].

All in all, hundreds of thousands of tests were carried out [1].

Throughout the testing, small refinements to the design emerged, such as officially changing the spelling of the word Alpha to Alfa, and Juliet to Juliett to avoid pronunciation variations across languages.

The Final Push by NATO

Urgency for a final, and generally accepted phonetic alphabet had heightened by the time the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) was founded in 1949 (right as ICAO and Prof. Vinay were finishing a systematically-derived phonetic alphabet) [4]. With NATO, various state’s militaries were expected to function as one in the “event of a seemingly imminent all out war against the Warsaw Pact.” [4] In early 1956 NATO adopted ICAO’s refined alphabet, but modified one word (Nectar to November). From the moment of NATO’s adoption and simple change to the letter N, the NATO phonetic alphabet became quickly adopted by numerous international agencies including ICAO.

Though the phonetic alphabet adopted by NATO was primarily derived from systematic testing involving hundreds of thousands of tests, it is clear that part of the alphabet’s rapid spread and its ability to endure the decades was due to NATO pushing the implementation of the standard.

Regional Adaptation, as Needed

Although the NATO phonetic alphabet is the standard, and it has not officially changed, regional adaptations have been made for various reasons. Delta, India, Lima, and Whiskey have experienced such adaptations.

In Atlanta, where the Delta Airlines headquarters is, Delta may be replaced by David or Dixie. In Pakistan, where there are historical and ongoing conflicts with India, the word is replaced by Italy, or Indigo. Lima means five in Malay, so Lima is replaced by London in countries where Malay is an official language. And in Muslim countries, where alcohol is more prohibited, Whiskey is replaced by White or Washington [1].

Concluding Remarks and Socio-technical Inertia

As we have examined the NATO phonetic alphabet, it seems unfair to call it by NATO’s name. Especially given that the vast majority of its systematic development was carried out by ICAO working with the US Air Force and various academic institutes. Nevertheless, the rapid and widespread adoption did not happen until NATO had embraced ICAO’s alphabet with one minor change (Nectar to November).

So what made the NATO phonetic alphabet good? In short, the alphabet adequately solved a widely-observed problem. It did so under ICAO’s multinational organization which involved many global stakeholders. The design was the result of significant systematic test and statistical analysis [4]. And the alphabet was adopted by an influential quasi-global organization (NATO), which pushed for its international acceptance.

Although the NATO phonetic alphabet underwent significant testing and refinement in its development, it is worth considering the role of sociotechnical inertia when trying to assess its longevity. Like the QWERTY keyboard, the NATO phonetic alphabet has become deeply embedded in our society, so much so that new and improved systems are unlikely to debunk it.

Nevertheless, the NATO phonetic alphabet works, and given the variety of alphabets that preceded it, we can conclude that it works well. Converging on a globally-accepted design was not trivial. It required organizations like the US Air Force to look past its own cultural lense and to involve stakeholders who experience the world differently. It required metric-based testing and analysis to be planned, executed, and interpreted. And its success most likely required a top-down roll-out by a powerful organization as large as NATO to achieve widespread, rapid, acceptance.

References

[1] NATO phonetic alphabet, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/NATO_phonetic_alphabet, accessed 11 Aug 2022.

[2] Pilot Institute, “How to Use the ICAO Aviation Alphabet,” https://pilotinstitute.com/aviation-alphabet/, accessed 11 Aug 2022.

[3] Allied Military Phonetic Spelling Alphabets, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Allied_military_phonetic_spelling_alphabets#Royal_Navy_radiotelephony_spelling_alphabet, accessed 11 Aug 2022.

[4] S. Lichtman, “From ‘Able-Baker’ to Today,” Leatherneck, December 2020, https://mca-marines.org/wp-content/uploads/From-Able-Baker-to-Modern-Day.pdf, accessed 11 Aug 2022.

[5] Telephone, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Telephone, accessed 11 Aug 2022.

[6] Long Distance, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Long-distance_calling, accessed 11 Aug 2022.

[7] Telephone Spelling Alphabets, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spelling_alphabet#Telephone_spelling_alphabets, accessed 11 Aug 2022.

[8] A. Spink, “From Butter to Bravo – a brief history of the phonetic spelling alphabet,” NATS, April 2020, https://nats.aero/blog/2020/04/from-butter-to-bravo-a-brief-history-of-the-phonetic-spelling-alphabet/, accessed 11 Aug 2022.

[9] H. M. Moser, “The Evolution and Rationale of the ICAO (International Civil Aviation Organization) Word-Spelling Alphabet,” US Air Force Technical Report, July 1959, https://web.archive.org/web/20160310112903/http://www.governmentattic.org/4docs/ICAO-WordSpellingAlphabet_1959.pdf, accessed 11 Aug 2022.

[10] Chicago Convention on International Civil Aviation, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chicago_Convention_on_International_Civil_Aviation, accessed 11 Aug 2022.

[11] International Civil Aviation Organization, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_Civil_Aviation_Organization, accessed 11 Aug 2022.

To cite this article:

Mattson, Chris. “Good Design: Alfa, Bravo, Charlie, and The Phonetic Alphabet.” The BYU Design Review, 11 Aug. 2022, https://www.designreview.byu.edu/collections/good-design-alfa-bravo-charlie-and-the-phonetic-alphabet.